2.5 School education: Zen roots and ukereiru in the menu

Sachiko: Japanese cuisine is not only delicious and beautifully presented, but also regarded as very healthy.

In Japan, a healthy approach to eating starts in childhood at school. School lunches (known as kyushoku 給食) are developed in each prefecture by nutritionists and dieticians. These are put into place in public elementary schools. School lunches are rooted in Japanese cultural traditions: “The first school lunch in Japan was started by a Buddhist monk who oversaw a school in Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture.

School lunches in Japan became so much a part of what it means to educate a child that in 1954 the government enacted a School Lunch Act: “School lunch was recognized as a legitimate part of children’s education as a way to teach knowledge about how food is produced and important dining customs,” according to a 2015 article in Japan Times. […]

OK, but what exactly are the kids eating? Menus vary from prefecture to prefecture, based on seasons and local products: balance, freshness, and small portions.

Nourishing Japan, a website that focuses on Japanese school lunches, lists a range of typical school lunches, which invariably include a protein (fish, soybeans, chicken, liver), a starch (noodles or rice), and two vegetables. A Japanese school lunch is organized, in part, by color. Nourishing Japan notes: The Japanese have concocted their own way to teach children about their food… They’ve grouped it into three categories: red, yellow and green. This group of three is regularly included in the school lunch menu explanation: RED: Chicken, tofu, milk, herring and seaweed YELLOW: Rice, potato, flour, yam, and mayonnaise GREEN: Carrots, burdock root, soybeans, Napa cabbage, cucumber, daikon, and dried mushrooms. I thought of Dogen and his colors. “Is this true, Yumi? Is this typical?” “Yes,” Yumi explained. “Red for protein, yellow for carbohydrates, and green for vitamin. We remember these foods by their functions, namely, food that builds our body (protein), food that generates energy (carbohydrates), and food that conditions our body (vitamins). (page 178-180)

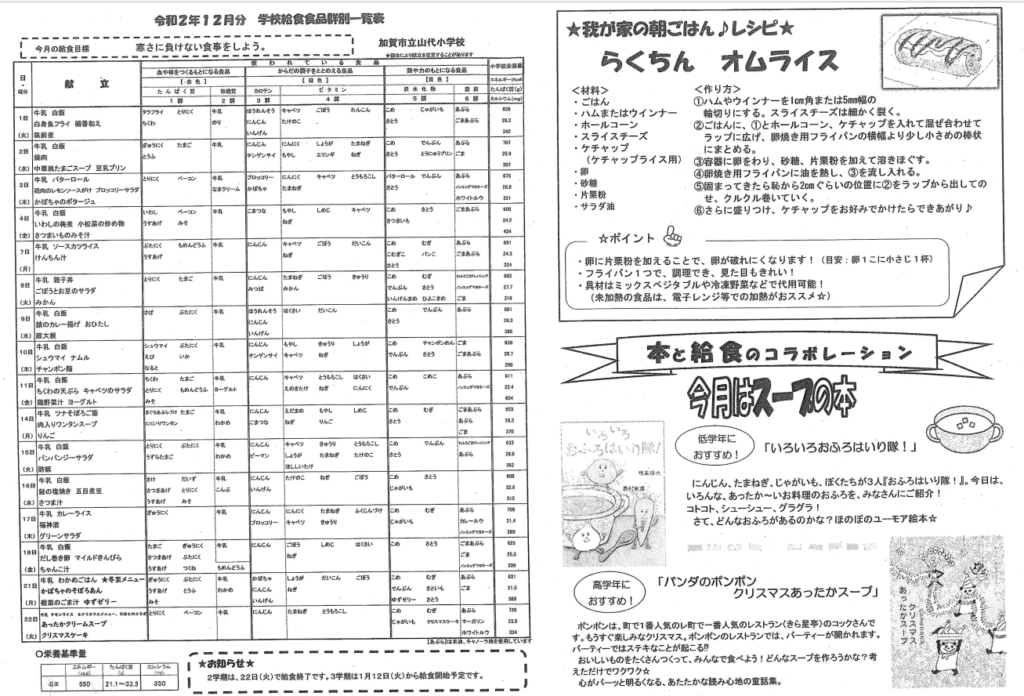

When I was a student, I had my lunch at school every day. Then, I have been an elementary school teacher for five years, before getting married and eventually becoming Beniya Mukayu’s proprietress, so I had lunch at the school during that time too. So, I know school lunch quite well. I love yakisoba焼きそばand the day when it was on the menu, the children in charge were coming to me with a big portion. The lunch was delicious and the nutritional balance was well thought out. Today it’s still the same. I have checked a few month’s lunch menu at Yamashiro Elementary School山代小学校: it consists of rice, milk, entrees, soups, stir-fried vegetables, simmered dishes and salads. This is the paper that has been given to the children and their parents for December 2020.

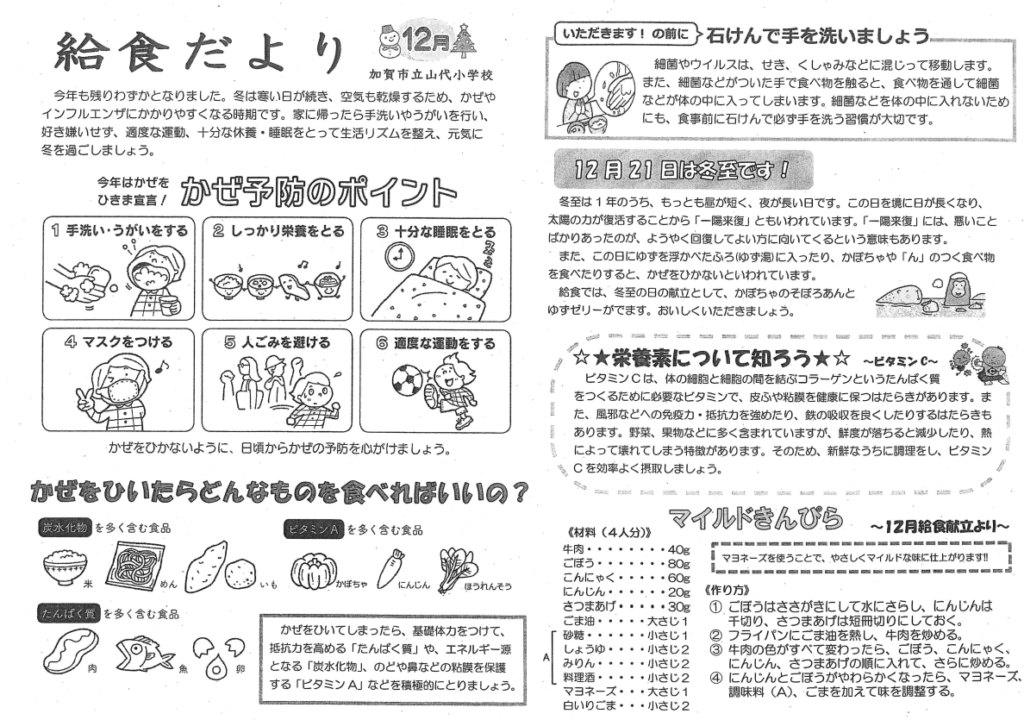

On the front left page, the first line is a statement on a sort of “goal” for the month, it reads: “Let’s eat to overcome coldness!”, below, the menu in December. On the top right page, some suggestions to the parents on how to make a good breakfast. Below, introducing a book on soups. Then, printed on the back of the same sheet of paper, there is a sort of letter on how to prevent catching cold: what food should we eat to prevent cold?

Moreover, the school menu reflects the food traditions: for example, the menu for toji 冬至 (which always falls around December 21st, winter solstice) toji is the day when the sun comes to the lowest position of the year and the night is the longest in the Northern Hemisphere. Traditionally, Japanese eat pumpkin because it is nutritious and it is said to prevent colds and diseases if eaten on that day.

So, the main dish of the school lunch menu on toji this year is pumpkin soboro anそぼろあん (pumpkin and minced chicken meat simmered in dashi). You can see that the sense of the season is important even in school lunch menu!

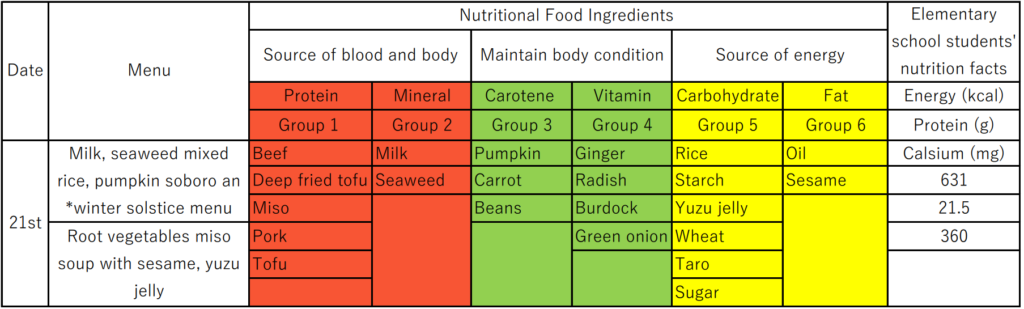

Let me explain the Japanese school lunch in this particular day:

December 21st: menu

Milk

Wakame rice

Winter solstice menu: pumpkin soboro an

Mixed roots soup with sesame

Yuzu jelly

On Yamashiro’s elementary school menu, food is divided into three main categories, by color, each of them having two subcategories. On December 21st, for example, red for protein and inorganic which build our blood and body, such as beef, pork, deep-fried tofu, miso, milk and wakame seaweed; green for vitamin and carotene conditioning our body, such as ginger, daikon radish, burdock, green onion, pumpkin, carrot and green beans; yellow for carbohydrates and fat which generate energy, such as rice, wheat, starch, taro, yuzu, citrus jelly, sugar, oil and sesame. Eight hundred years ago, Dogen conceived the concepts of goshoku, it is amazing that the color theory devised in the 13th century is still currently used!

Scott: It’s very balanced. It’s very healthy. Another word I should say is “mindful”. In addition to Dogen’s thinking about how the food is prepared, it inspires the person who is enjoying the food to think about it also, so you are not just eating like an animal, you are thinking about what you eat while you eat. You are thinking about the colors, you are thinking about the flavours, you are thinking about the season. You might even think about the animal sacrificed for your pleasure. If you are thinking about what you eat – I think – you are eating more slowly, and you don’t eat so much. One of the things that people talk about for people who have problems with eating, it is called mindfulness, they want to teach people to eat more slowly, think about what you are eating, and so on. And if you eat slowly, as I said, you won’t eat so much, you know what I mean, you’re savoring the tastes and textures… And that’s the other very healthy thing about the Japanese diet: the portions. The caloric intake for a Japanese person compared to a Northern American is 40% less on average. People eat less in Japan. Sometimes, when I am out with my wife or some North American friends visiting Tokyo or Kyoto, we watch the Japanese men and women, but especially women, they are eating a lot of food. My friends often say: “How can the Japanese women be so thin and eat so much food?” And I reply: “Because they don’t eat all day. And also the food they are eating is not heavy, big pieces of food, it’s a small amount of food and it’s very flavourful and they eat as much as they want, but they do not have snacks (cookies and candies and potato chips) during the day.” As a result, when people go out to eat in Japan they really enjoy and again…in restaurants in Europe and in the States the portions are so big… So part of the thing with Dogen and the school lunches is that the traditional Japanese diet shows children from a very young age: you don’t have to have a hamburger. It’s okay, if you want a hamburger it’s fine, enjoy yourself, but there are other things that we want to introduce you to. We want to introduce you to the pumpkin for the season, we want to introduce you to the colours… there is communication between the food and the person, the food is talking to you.

Sachiko: Talking about mindfulness, it starts even before eating. If you prepare the food mindfully, even when you shop mindfully, paying attention to the seasons but also, if you have the chance, getting to know who the suppliers are. There are some places here in Yamashiro Onsen where you can get food and you know exactly who has been growing that. That’s mindfulness in a very broad meaning, and it also connects to sustainability because you make your choice from the ingredients, how to cook them, how to eat them, it goes to a lot of stages and it’s mindfulness in a very broad way.

Scott: I completely agree and that also goes back to what we were all talking about a while ago, which is: “What do visitors want?” The issue of mindfulness and producers of food are a big concern of North Americans and Europeans now, even before the pandemic. And again, it doesn’t have to be luxury necessarily. Many people are buying “farm shares” so you will buy a share from a farm and every week the farm gives you a box of really fresh food that is often organic. And because many people want to know where the food comes from, and how it is grown, when you go to a restaurant in Switzerland, for example, they will note the meat is from Argentina, the meat is from Switzerland and so on. People are more and more interested in where the products come from and so, especially at a ryokan or at a fancy restaurant in Kyoto or Tokyo people love to know a little bit more about where the source was, not just for reasons of health but because the food tells a story. It tells a story on how the food was produced and how it was grown. It’s a very important part of what people who are travelling now want from a dining experience.