3.5 Appreciating nature’s changes and the present moment

Sachiko: In 2020, the Japanese government declared the state of emergency due to Coronavirus for the first time, so we had to close the ryokan at the end of March/beginning of April. It was a time of great uncertainty and worry, we did not know when we could open again and when the guests would come back, although it was one of the best times for visiting us. In spring, the nature in the forest garden is really vibrant, you can feel the new life everywhere: in the grass, in the buds, the insects that are flying around, you can feel the warmth of the sunlight on your skin again after many cold winter days… Even if the ryokan was closed, we were working on a project called “Stay home with Beniya Mukayu Team” and one morning, during a video-making session on the terrace facing the forest garden, I suddenly felt deeply inside myself the vibrancy of the surrounding nature and thought: “Look, it’s a perfect spring day despite the Coronavirus. It’s a shame that we do not have guests enjoying it too!”

The spirit of Japanese hospitality is based on our sensitivity towards nature. As you wrote:

Japanese also make note of twenty-four very short seasons, known as 24 sekki 節季, some lasting only a few days. Because of the brevity, the observer has to pay close attention or will miss out. (page 111-112)

So I felt sad that the value of the ephemeral beauty of that short season was passing away without being noticed by any guests. After the video-making session, I went to Wakamurasaki suite room. The mountain sakura was in bloom. I sat on one of the armchairs in the bamboo veranda and contemplate it. Facing the sakura tree in bloom, I tuned in with the new life that was pushing to emerge and felt rejuvenated. It made it easier for me to accept the pandemic. Thanks to nature, I felt calm. To me, nature is always a source of peace of mind, even in difficult times. Scott, did you have any similar experience?

Scott: When I’m lucky, and I try hard to be lucky, this happens often, yes. I live part of each year in a village of three hundred people deep in the Glarus Alps of Switzerland. No cars, seven farms, lots of cows on hiking paths in three seasons, winter of snow as high as two meters. Storms, rain, clear skies, the air is clean, and you can see birds and hear the sound of brooks. Otherwise, I live in a city and when I’m stressed, I try to recall what I see in the mountains, which of course has a calming effect.

Sachiko: Going back to your book, I especially like your idea that

Take the time to do something with nature—anything—that involves interacting with what you see and hear. It could be watching birds and learning their calls, or getting to know the types of trees in your neighborhood. Allow nature to become part of your vocabulary, and you’re going to find that the human voice is only one source of stimulation, and not the most powerful one by any means. (page 112)

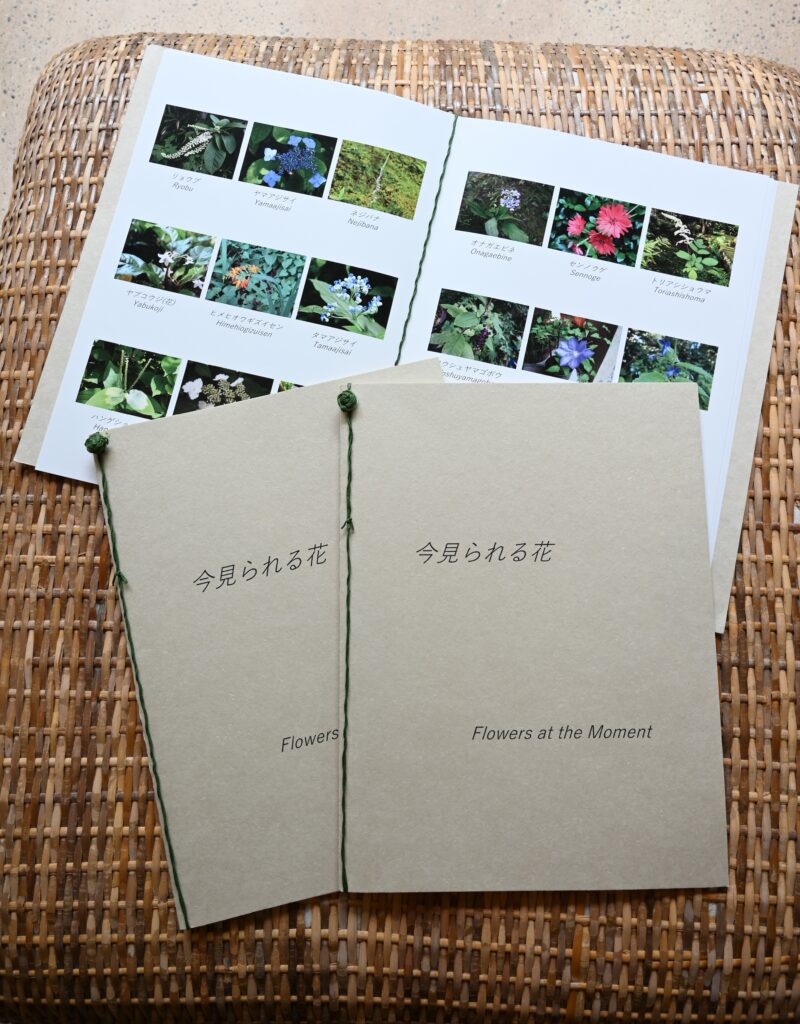

This is also what we do at Beniya Mukayu. We encourage our guests to notice the nature around to become more aware of the present. That is why in each room there are two little books illustrating the nature around Beniya Mukayu. One focuses on the seasonal flowers and natural plants that one sees outdoor as well as indoor, in the rooms and in the lobby; the other is about what guest can see when taking a stroll in our forest garden: trees, mosses, flowers. I think this is unique to Beniya Mukayu. I have never heard about anything similar in other ryokan or hotels in Japan… I really cherish these two little books, because if you know the names of the flowers, plants, trees and mosses, it’s easier to befriend them, isn’t it? Scott, how do you think this idea as a psychologist? If we know the name of trees, plants or flowers, we could feel the nature closer like friends?

Scott: Absolutely! It’s a way of pretending to organize one’s life, and can create a real sense of belonging. It’s like naming things in your house. By naming tress, plants, and flowers, we can feel more at home in their world, more like a guest of nature rather than its master. It’s to show respect. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that we must respect and protect nature. Nature is in charge. If you don’t accept and name nature’s authority, you’ll be very sorry because nature always wins. I can see how your background as an elementary school teacher is reflected in the two books, because in a way, teaching the guests about the nature is a little bit like taking a class of children for a lesson in a park and ask them: “Who is going to tell me the name of that bird?”