5.4 Nothingness and Mukayu: richness in emptiness

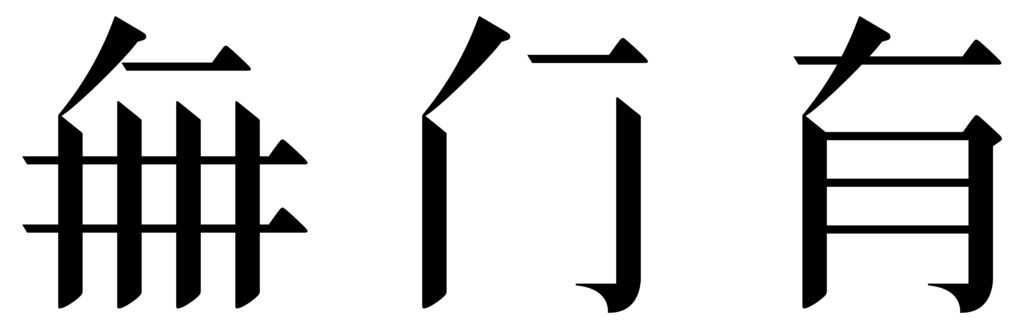

Nearby is another ryokan, Beniya Mukayu, where the name itself is a sign of the outlook that informs Japanese use of space. Sachiko Nakamichi, who owns the property with her husband, Kazunari, told me that mukayu means, more or less, “everything is nothing.” What you experience here, too, are bare walls and silence. (page 142)

Sachiko: As you write, the name itself is a sign of the outlook that informs Japanese use of space.

The concept of Mukayu is “richness in emptiness” and it is inspired by Zen philosophy too. Beniya Mukayu was born from the vision of a besso, a villa, which Kazunari and I, along with the architect Sey Takeyama, see as the perfect place for feeling part of nature. The concept of emptiness is very important for Sey Takeyama, it informs almost all his projects, but Beniya is the only one where Takeyama has actually openly expressed this concept in the name too. Kazunari and I are very honored that he did so.

Yes, I told you that Mukayu means, more or less, “everything is nothing.” but I also would like to add that “nothing is everything”: precisely because of this, one can feel the potential. The concept of Mukayu can be hard to grasp at first, especially if someone has never been at Beniya Mukayu, so let me quote a passage from one of the texts that better explain nothingness at Beniya Mukayu:

A vessel that’s empty has the possibility, precisely because it is empty, to hold things inside. In the same way, abundance lies in possibility—that possibility that exists before anything occurs. This philosophy, in which the potential of possibility is seen as power, has been common to China and Japan since ancient times. Takeyama designed this annex with the concept of evoking the power of the potentiality of “nothingness” and so named it.

Kenya Hara. (2007). DESIGNING DESIGN. Japan: Lars Müller Publishers.

This passage by Kenya Hara was published in 2007. After that, Beniya Mukayu underwent further changes, and now I can say with confidence that it applies to the whole ryokan and not only to the annex…

Scott: I just read a book called How to be bored by Eva Hoffman. She is an historian in Canada but I think she is from Poland originally. What she talks about a lot in her book is, the idea of doing nothing and how important that is for creativity. You should not occupy your time, you should not try to fill in the time with things, you should try not to do anything. It’s hard to do that. I don’t agree with this part: she said it’s hard because of the internet. I think it has always been difficult. Maybe the internet makes it more difficult, but I don’t think that in history people have been very good in doing nothing. I think there is too much stress and one way to alleviate stress is to externalize it, to create problems.

Sachiko: Can you explain us a little bit better about this?

Scott: I think that when people are bored, they get in touch with emotions that they are uncomfortable with, they have feelings, thoughts, memories that are upsetting to them. So, rather than think about them, accept and dwell on them, they create an external conflict. If I’m feeling good about myself, and I’m feeling a sense of well-being, happiness or contentment, I don’t fight with people you know? I don’t argue with anybody. But if I am unhappy in my heart, or if I am having a bad memory, then I am going to be irritable, I am going to be more reactive, I am going to be more difficult. That is what I mean by ‘externalizing it’. But if you spend more time accepting who you are, you don’t feel the need to create external conflicts, the conflicts are all inside you. And I think for a lot of people going to a ryokan or going to the D.T. Suzuki Museum is difficult because they get in touch with feelings and thoughts they try to avoid. So it’s similar, it’s really similar. One of the things one may think about in introducing ryokan to people who don’t know what they are, is to explain the benefits. People do not know what it is, they don’t know what it is. There are people who go to Zen retreats, and then there are people who go hiking in the mountains, that is very similar to that: in other words, if you can understand that being at a ryokan – a beautiful ryokan, not any ryokan – creates a safe environment where you can accept whatever you think is so difficult to accept. In other words, whatever you are afraid of, or whatever it is you are sad about, it’s not that bad, it’s what makes us humans. Accepting the things about ourselves that are the most painful, the things that we are ashamed of, once we can do that, we become more comfortable in our skins, we become more relaxed. And so that’s something magical about a ryokan, you are with complete strangers and you are unclothed, or you are in the tatami room where you sleep and it is really quiet and there is nothing on the wall and it’s so peaceful… maybe in the summer you open the glass door and you hear the sounds of nature or in the winter you wake up really early because maybe you are jet-legged and you go out and the snow is falling it’s so nice, it’s so nice… if you are comfortable doing nothing. It’s very powerful. And in Japan I read that hundred years ago that some famous Japanese writers would go to the ryokan to stay there and write because they have no distractions, they were able to think and to feel more alive. Like the book Snow country 雪国 by Yasunari Kawabata川端康成 takes place in a ryokan, so there is something about the ryokan… How’s this? If the artists understand its value, those of us who are not artists like Kawabata can also accept… in fact, you may ask yourself, what did Kawabata think that was so special about it? What did he find that was important for his development as an artist? So you can also develop the art inside yourself… I mean: the great artists are the ones who accept the things about themselves that they don’t like. When you read a great novel, or you read a great work of non-fiction, even, it’s very honest, and when you are at a ryokan there is a sense of being honest. When you go to the onsen you are not wearing a bathing suit, or when you are in your tatami room, when you are sleeping, as I said there is nothing on the wall, it can make you feel more alive.

Sachiko: I agree and I also would like to add that Takeyama and I discussed this too. In 2018 Takeyama has designed the Byakuroku suite, which features a studio between the bath and terrace, facing the garden. Takeyama conceived it as a space for creative imagination or meditative thought coming from a refreshed mind. Indeed, creativity is nurtured by nature, silence, beauty…

Scott: I think so.

Sachiko: Takeyama has designed the architecture of Beniya Mukayu and I take care of the shitsuraeしつらえ. Japanese architecture is often associated with minimalism, true, but in the case of Beniya Mukayu, it is not just about taking off (like you have done in your studio!). As for my shitsurae, I don’t decorate, I don’t add, I just connect the outside with the inside so that every single detail is part of a greater harmony. It’s more about creating indoor spaces that are very comfortable for the outside to come in very gently and very smoothly. By ‘outside’ I mean: the scenery, the breeze, shadow and light, and maybe even gods…

I have already said a lot about my shitsurae, but after hearing your words today, I noticed that maybe my shitsurae allows the guests who come to Beniya Mukayu take off everything. At Beniya Mukayu you can take off your clothes in the public bath and your circumstances and your business or everything. Taking off everything makes you naked not only in the public bath but also in the room… Once you become naked you will find something occurs from the bottom of your body or from the bottom of your heart. This is the purpose of my shitsurae, I noticed this now. I think so.

Sachiko: If there is something very offensive, or it’s very dirty or not beautiful, you could not be naked. Making everything smooth and in harmony, you can feel like a child and so you can be very easily naked. So maybe one of the purposes of my shitsurae is that. Everything is calm and in harmony with nature, nothing offensive, nothing strong, nothing angry, you can feel like a child and be at ease even when you are naked.

Scott: That’s right. And you feel it’s okay because you are creating a safe environment.

Sachiko: Very safe. Safe is a good word.

Scott: Right. When you see a child that looks happy, that child feels safe.

Sachiko: Yes.

Scott: You worked with children so you know, you can tell when a child is in a house where he’s not safe, you see it in his face.

Sachiko: I understand. I understand very well.

Scott: What the ryokan does is to – well, you have – create a safe place where people can just be themselves, and that is really not typical. It’s not typical. It’s a very different experience. That’s important when you describe what a ryokan is to people who do not know what it is, it’s a little bit like being reborn, you can feel revived. I can tell you this: when I go to a nice ryokan for two nights, I leave there and I feel so relaxed, really relaxed, different than a resort on a beach, different than a beautiful, fancy hotel, because there is something about slowing down. And when I think about the walls in the rooms at Beniya Mukayu, with the straw, that’s magical, that’s really cool, and so that gives the guests a feeling of being closer to nature. It’s these little elements that keep adding up, it’s an attention to detail.

Sachiko: Everything here reflects the way in which we Japanese accept and appreciate the brevity of life. The windows of every room are opened wide onto the garden, allowing light and shadow to pour in. The wooden private baths are always filled to the brim with hot water reflecting the trees in the garden as in a mirror. There are no hanging scrolls in the alcove – the scroll creates a sort of detached microcosm – instead, in the alcove there are only flowers that one can also find in the forest garden outside. The flowers themselves are seasonal, not gorgeous: this is one of the ways to allow the outside to come inside very easily. The small tables between the armchairs in the bamboo veranda are also very important for allowing the outside to come inside. I’ve chosen glass tabletops so that the scenery of the garden could come in through the window and reflect on the tabletops.

The idea behind is to always have open window, to always being as closer as possible to nature. Similarly, the colors and the materials all match the outside scenery. They are as close to nature as possible. For instance, the floor of the lobby is made of clay from the Noto peninsula that thousands of years ago was at the bottom of the Sea of Japan. It is very unique. Hotels usually have carpets or marble floors! The plaster of the walls is also made of clay mixed with straw. When Takeyama and I chose the amount and the size of the straw to use, we considered how they would affect the interplay of light and shadow on the plastered walls… There is another text by Kenya Hara that explain all this from the guests’ point of view:

When I stay at a high-quality ryokan, I feel my sensitivity rise several degrees. This is because both mind and body can relax, since scrupulous attention is paid to the space. The standard for arrangement and accessories is the distribution of a minimal number of objects. Precisely because there are very few things in the room, my eyes are drawn to the beauty of the woven surface of the tatami mats, and I am enticed by the appearance of the plaster of the walls. My eyes turn to the flowers arranged in a vase in the alcove, and I am able to fully enjoy the beauty of the dishes on which the meal is arrayed. My conscious mind spontaneously opens up to the natural world represented in the garden. (Kenya Hara, Designing Japan, published by Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, page 81)